The Scientific Method: Do We Need A New Framework?

Is it time for a new framework in science education?

Everyone knows the scientific method, right? You probably first learned it in elementary school – that simple set of steps that, when you follow them in the right order, means you have successfully done science. The exact steps can vary slightly, but they usually include the following: observation, question, hypothesis, experiment, analysis, and conclusion – in that order. All sorts of science classes and programs teach the scientific method; posters, science experiment kits, and educational books often include it as a colorful, but unidirectional, flowchart. This scientific method is certainly not reserved for kids – it is often taught even in higher education. Check out an intro college science textbook and you’ll probably find that same flowchart (albeit less colorful) on the first page.

The scientific method’s origin story

Given its ubiquitousness, you might think the scientific method was as old as science itself. In fact, “the scientific method” as it appears today did not exist until the early 20th century. It was popularized largely by the expansion of public schooling and the textbook industry, which took inspiration from a description of “a complete act of thought” by philosopher John Dewey. Dewey himself was a science educator, and did not endorse this use of his work. The scientific method has been controversial from the beginning – a committee of Harvard scientists released the following criticism of the new method:

“Nothing could be more stultifying, and, perhaps more important, nothing is further from the procedure of the scientist than a rigorous tabular progression through the supposed ‘steps’ of the scientific method, with perhaps the further requirement that the student not only memorize but follow this sequence in his attempt to understand natural phenomena.”

These complaints were not unique – many scientists and science educators immediately rejected the scientific method as far too limiting and unrealistic. It was too late.

The problem with the scientific method

The influence of the scientific method has grown since its invention, and at face value, it doesn’t seem like a bad way of describing the processes of science. Yet many scientists and science scholars continue to set themselves against it.

One common criticism is that the scientific method is often used not only as a teaching tool but as a justification for the validity of scientific information. Educators and science communicators often point to the supposed infallibility of the scientific method when trying to explain why it is important to trust science. If you follow those steps, and remain impartial, you will create viable scientific data. Unfortunately, this just is not true.

First, most scientists don’t follow the scientific method at all. Many modern sciences don’t involve any form of experimentation, and scientists often don’t form hypotheses until well into an investigation. Think about the entire field of earth science – there are only so many experiments you can do when you’re studying things that happened billions of years ago or hundreds of miles below your feet. For example, predicting the likely eruption type of a volcano involves using knowledge from other sciences, such as chemistry and physics, and applying that information to observations and measurements about the composition of that volcano. There is no experimentation, hypothesizing, or result-gathering in this situation, but it could produce vital information. Many other sciences also rely heavily on data sources other than experimentation. Social sciences often use surveys. Economics relies on abstract models to predict real-world outcomes.

Second, science is not perfect, and it is far more complicated than the scientific method implies. In our increasingly technology-driven and complex world, it is becoming more and more important for the average citizen to have a basic understanding of science, including an understanding of why it is trustworthy. Unfortunately, the scientific method we learn in school does not adequately describe the many processes of science, or the uncertainty inherent in the production of scientific knowledge. There is no allowance for retrials, or for the influence of new data on existing research, or for the admission of mistakes. This uncertainty is all part of the process that leads toward consensus. It’s completely normal, and it doesn’t look anything like that flowchart in your textbook.

However, when you have been educated to believe that good science must follow the scientific method, and also that the steps of that method are the center of science’s authority, it can be frightening and confusing to observe the reality of the scientific process and difficult to believe the results. As we have seen during the COVID pandemic, real science generally does not follow the steps of the scientific method. Since there was no time for scientists to reach full consensus before releasing data, the uncertainty and changeability of science became far more obvious than usual. We saw a noticeable increase in science denial during and after the pandemic–perhaps a more realistic and flexible model for science education could help prevent future generations from rejecting the validity of science that does not fit a limited and unrealistic method.

It’s time to reconsider teaching the scientific method

What people need to know are the real reasons they should trust science: verification through the peer review process, the slow creation of scientific consensus, and the accumulation of scientific expertise through years of questioning and research. Communication and collaboration on a massive scale make modern science effective, and scientific information should be trusted because of the ways it is verified, not the way it is produced. Of course, we should not put complete and blind trust in anything. However, an understanding of the processes of verification and consensus along with a decent baseline of factual science education would provide a solid basis for informed trust in the sciences.

Some newer programs are embracing the research demonstrating that the scientific method is problematic. The Next Generation Science Standards encourage schools to avoid teaching the scientific method. Instead, they recommend describing science as a set of practices and using examples from different fields and methods to demonstrate the true breadth of scientific inquiry.

Although curricula and educational standards like the NGSS are moving in the right direction, more work remains to remove the scientific method from its pedestal. Good science education is vital, and a first step in that education (especially for older students) should be a genuine and realistic depiction of modern science, not an oversimplified set of steps.

This article is adapted from my undergraduate thesis. You can read the full paper here.

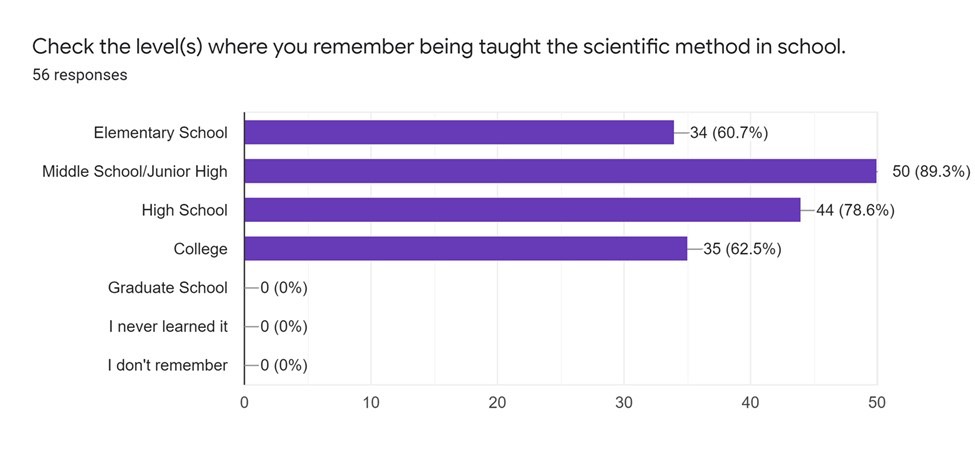

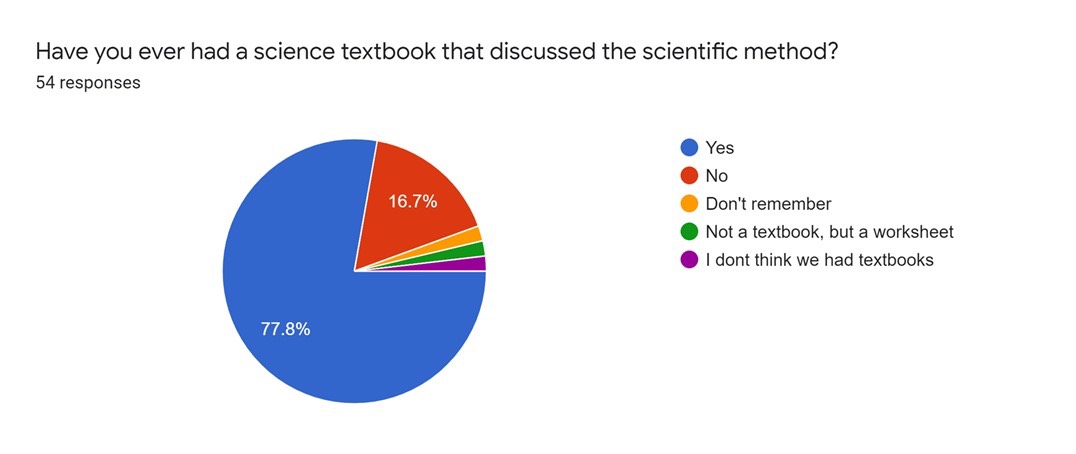

Some figures from the study I did during my thesis research:

A chart outlining where individuals remember being taught the scientific method in school.

A pie chart demonstrating the percentages of people who have had a science textbook that discussed the scientific method.